AYUNGIN SHOAL

The Philippines' military outpost in the South China Sea

1309 HOURS

VILLAMOR AIRBASE

“I understand that during my participation in this Media Coverage of the Ayungin Shoal, I may be exposed to a variety of hazards and risks, foreseen or unforeseen which are inherent in all media coverage and cannot be eliminated without destroying the unique character of the activity.

“These inherent risks include, but are not limited to, the dangers of serious personal injury, property damage, and death from exposure to the hazards of travel and the Armed Forces of the Philippine has not tried to contradict or minimize the understanding of these risks.

“I further understand that on this mission, there may not be rescue or medical facilities or expertise necessary to deal with the Injuries and Damages to which I may be exposed.”

It was a waiver that rattled every intuitive bone in my body.

“Did you sign? Should we sign?,” asked my cameraman, Angel Valderrama. It was difficult to say yes, knowing I was responsible for their safety, and that Angel had already barely escaped from a life-threatening situation once before. How can I tell them to sign off on a document that says we understand and accept that we are entering hostile territory, and that we can blame no one but ourselves if we perish at sea?

“We should sign, if we want to go to Ayungin,” I said, and took the pen. I felt Angel hesitate beside me. He could have refused, and I would have let him. But then he took the pen from my hand, and signed. He was in.

WESTERN MINDANAO COMMAND

PUERTO PRINCESA CITY, PALAWAN

The mission was described to me as nothing short of covert, and that we were to agree to the clandestine terms completely, or not go at all. We were instructed to stop sending calls or messages the moment we landed in Palawan, because Chinese intelligence was already capable of intercepting communication from there.

The 19 journalists communicated to their respective news desks in code, talking about parties and picnics when they really meant the voyage to Ayungin. It would take at least 30 hours just to get to the “picnic.” Our office needed to know, in one way or another, that we would be purposely off the radar for the next several days.

PALAWAN

Darkness fell, and the journalists boarded one of the many different vessels that would take us to Ayungin Shoal. When the boat left the dock, soldiers ordered all camera lights off. Silence fell over the jovial group, each one lost in their own thoughts as our boat cruised passed lights we could no longer ask about nor identify.

I opened my mobile phone, sending a final cryptic message to the news desk, hoping they would understand what it meant:

“Lalangoy lang ako, ah.”

SOMEWHERE OFF THE COAST OF PALAWAN

The boat stopped, somewhere in the water. It was too dark to tell where we were. A soldier approached us, and told us to divide ourselves into two groups. Lit by floodlights in the rear, we caught sight of the two vessels that would make a run for Ayungin Shoal: the AM 700 research vessel, and the wooden fishing vessel ML Unaizah May.

The journalists asked why we needed to split up, when each of the two vessels could clearly accommodate all of us. No one answered the question. It was classified, they said. Unsettled by the shroud of secrecy, the journalists huddled, and played out the imagined scenarios in our heads. Could one of these vessels be a decoy? What role is the media really playing in this mission?

It was clear that voyaging in two groups would raise the chances of at least one of them making it to Ayungin Shoal. But should one of these vessels fail in its mission, we could not allow our news coverage to fail with it. The military mission, of course, is separate from ours.

My team decided to separate - I boarded the AM700 with my small camera, while Angel and his assistant, Ronilo Dano, threw their luggage and the rest of the equipment onto the ML Unaizah May. No matter which of these vessels would succeed, what mattered was that an ABS-CBN journalist would be there.

In the dead of night, with more questions floating than there were answers provided, the 36 and a half hour voyage to Ayungin Shoal began.

1000 HOURS

WEST PHILIPPINE SEA

The first hours of voyage were uneventful. Nothing, not even my own imagination, broke the uninterrupted horizon of the West Philippine Sea. We sat at the beam or the side of the ship, talking about anything and everything, fighting boredom, battling seasickness. Our eyes would lazily scan the seas for anything interesting. A fishing boat perhaps. A dolphin or two. But there was nothing out there but us.

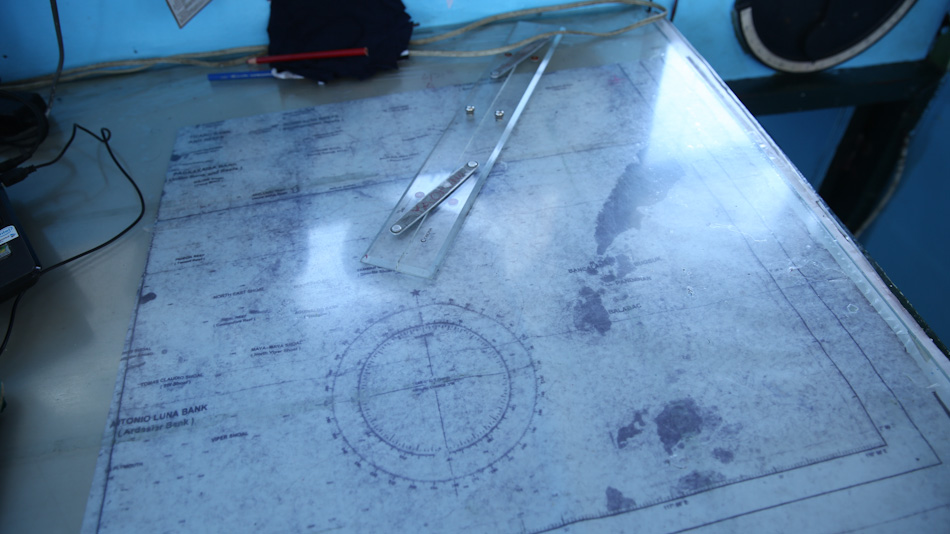

At the bridge of the AM700, someone else was scanning the horizon. But he wasn’t looking to break the monotony – he was scanning the seas for vessels that might want to block our path.

The man wore flip-flops, and knee-length shorts. He had on a bright green t-shirt that said “I Love NY,” and a towel was on his back, presumably to catch the sweat that never seemed to dry from the humid cabin air. Nothing in this appearance, nor in his boyish grin, betrayed his stature in the operation. But he is Lieutenant Senior Grade Ferdinand Gato of the Philippine Navy, the head of the Ayungin mission.

Gato, or “Gats” as he is fondly addressed, calls the shots in the operation, but he makes no spectacle of it. He is here to follow orders, and complete three missions.

“Ang mission ko, unang-una, ay madala `yung pagkain doon. `Yun ang pinakaimportante,” Gato said. He is referring to food, water, and supplies he loaded onto the two vessels, which he plans to deliver to the stationed Philippine troops on the Ayungin Shoal.

On March 9, 2014, almost three weeks before, a similar resupply mission attempted to reach BRP Sierra Madre, an old marooned ship that serves as the Philippine military base in Ayungin. Left there by the Philippine government in 1999, BRP Sierra Madre was strategically placed in order for the Philippines to efficiently defend the shoal, which the country claims as part of its sovereign territory.

But the March 9 resupply mission was blocked by a Chinese Coast Guard and turned back to Palawan. Since then, the AFP has resorted to airdropping supplies, just to prevent hunger in Ayungin Shoal.

Gato also brought with him soldiers who will replace the troops currently stationed at Ayungin Shoal. His second mission: to relieve from duty the nine exhausted Marines aboard the BRP Sierra Madre, who have been out there for nearly five months. These troops were only supposed to stay for three months, but the Chinese blockade again prevented their replacements from reaching the shoal.

With a wide grin, Gato revealed his third mission: making sure the journalists made it in, and made it out.

“Hindi nalalaman ng maraming Pilipino kung gaano kahirap ang magdala ng pagkain doon,” Gato explained. “Gusto naming makita niyo, para at least matulungan niyo kaming mai-share sa mga kapwa natin Pilipino `yung real na kundisyon nila doon.”

Three missions on board two ships that relied on one man to make it happen. “Gats” brushed off the importance of his role with a joke and a smile. But he said he would let nothing get in the way of the orders he was given.

Except, probably, fate. At 1235 hours, the AM700’s radio crackled, with a terse message from the ML Unaizah May:

“Medyo nagka-aberya kami dito, over.”

WEST PHILIPPINE SEA

Crewmen running about the ML Unaizah May roused the journalists from their sleep. They noticed that the ship had somehow come to a complete stop, and was being thrashed about by the waves.

They watched as one crew member tied a rope to his waist, and dove under the vessel. Within minutes, he brought the bad news back to the surface.

“Nakasayad yung propeller shaft! Nahulog!”

The propeller had been detached from the rest of the engine. Radio messages were exchanged.

ML UNAIZAH MAY: Hindi umiikot as per testing namin, umaandar yung reduction gear pero walang reaction, walang reaction, advise.

SUPPORT: Yung rudder, hindi magamit? Over.

ML UNAIZAH MAY: Rudder umiikot, rudder umiikot. Propeller namin ang ‘di umiikot, over.

SUPPORT: Roger naiintindihan kita, ang tanong ko ay kung nagagamit pa yung rudder, over.

ML UNAIZAH MAY: Umatras yung rudder namin, umatras, kasi putol yung shafting, putol yung shafting, over.

For more than two hours, the ML Unaizah May drifted dead in the water, while the AM700 circled it repeatedly, awaiting orders on what to do next. The journalists on the AM700 watched helplessly as their colleagues’ ship was being thrown about in the water. Nikko Dizon, a reporter of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, shouted an apology to photographer Grig Montegrande, whom she had asked to board the ML Unaizah May.

“Ay, grabe `yung listing niya. Oh my gosh… kawawa naman… Grig, sorry,” Dizon exclaimed.

Finally, at 1433 hours, the AM700 received orders to retrieve the journalists from the ML Unaizah May, and transfer them all on board. Team by team, a rubber boat picked them up, and shuttled them back to their waiting colleagues at the AM700. The rescued journalists were smiling, but pale and groggy. There would be no more energy to cover anything else that day.

With everyone aboard, the AM700 restarted its engine, leaving the ML Unaizah May adrift for another team to rescue. All the mission’s eggs were in one basket now. The success and failure of everyone now relied solely on this single boat.

WEST PHILIPPINE SEA

It is sunset. Without even the horizon to watch, many retreated into their sleeping areas for the night. Some who came from the ML Unaizah May were still so seasick that they couldn’t even eat dinner. At night, there was very little left to do in the ship but sleep.

But a shout from one of the cameramen sleeping outisde woke everyone up.

“May eroplano! May eroplano! Ang baba ng lipad!”

People jumped out of their blankets and bunks, half-asleep, in time to sea a pair of headlights descending from the sky, almost down to the level of the ship itself. The bright lights circled the AM700, flew back up, and down again.

Gato and his team wore night vision goggles in an effort to make out who it was. But the night was so dark that it could not be identified.

“Hindi natin ma-distinguish kung ano `yun eh,” said Lieutenant Junior Grade Erwin Nafarrete of the Philippine Navy. “Tingin ko ang purpose, kung military plane `yan. ay reconnaissance. Intelligence gathering, info gathering.”

Earlier in the day, passengers spotted several aircraft hovering over the two vessels. Bullit Marquez, a photographer of the Associated Press, was able to take a photograph of one of them. It bore the name US Navy.

Nafarrete, who has plied this route before, said this was the first time he had ever spotted American aircraft in the vicinity while steaming. But at times like this, he takes comfort in the presence of a friendly force.

“Syempre bilang ally ng US, bilang ordinaryong sundalong Pilipino, siyempre nagbu-boost ng morale natin. At least kahit papaano, alam natin na meron tayong kasama, tumutulong sa atin. Alam naman nating `yung China, powerful sila,” Nafarrete said.

Nafarrete, Gato, and the rest of the crew watched the mysterious headlights until it disappeared into the night. It would come again after two hours, and cause worry in the minds of the Filipinos on board who had no way of telling if it was friend, or foe.

0708 HOURS

VICINITY OF SABINA SHOAL

Re-energized from a night’s sleep, photographers and videographers woke up to catch a breathtakingly red sunrise. Reporters went about their domesticated duties, and washed dirty clothes with a water pump by the stern of the ship. The Marines who are to be left on the BRP Sierra Madre huddled outside the mess hall, sipping coffee as they watched the sky change its hue.

Today is the day we are set to reach the Ayungin Shoal. But the entire ship seemed so calm, for a day so big.

PAST SABINA SHOAL

Reports have come in that there are four Chinese Coast Guard vessels in the vicinity of Ayungin Shoal. These were the vessels we would have to be on alert for, whether they lock horns with us or not.

The journalists gathered at the ship’s forward to plan for the day. This was the agreement: for everyone’s safety, no one would make outside calls, nor break any story while still out at sea. But this agreement came with a very big exception: all deals are off, the moment China showed hostility towards the people on board the AM700. That would be the trigger for everyone to begin reporting what we saw, when we saw it.

But it gets tricky -- what is hostility, anyway? Is it an angry radio call, asking us to leave? Is it tailing the ship until the crew grows uncomfortable? Or can we only declare harassment, the moment they block our path?

“Harassment is different from blocking,” spoke Jim Gomez, correspondent for the Associated Press. “Pwedeng raradyuhan, umalis kayo, umalis kayo, pero wala pang blocking. So saan tayo pwedeng mag-file?”

“Baka magkamali, may ma-excite sa atin. Hindi mo masasabi naman talaga eh,” said Dizon, presenting the possibility that in the heat of the moment, one of us would cry harassment when there was none, and create further conflict.

It was then decided that we would let the Navy define what harassment was in the high seas. The media, using their respective broadcast equipment, could only report “any indication of harassment sa assessment [ng Philippine Navy]. Because we don’t know what’s normal, what is not,” I pitched in.

Once all the journalists agreed on those terms, Lt. (s.g.) Gato was called to the gathering.

“Yung bow ang tawag dyan, harapan,” said Gato, pointing to the front of the vessel. “Kailangan makita na naka-obstruct na yung vessel nila, para masabi natin na ayaw nila tayong papasukin.”

Gato continued, “’Pag nag-change course tayo, tapos bumalik sila uli, nag-change course tayo uli, pwede na kayo magbato ng message. Kasi yung first change course, baka naman nagkataon na dumaan sila doon. `Pag pangalawa, ibig sabihin sinasadya na tayo.”

VICINITY OF SABINA SHOAL

The atmosphere was still light on board, but more eyes were scanning the seas for any vessel on the horizon. Then, for the first time in more than 30 hours of travel, three black dots figured in the horizon on the starboard side. Everyone was on their feet. Could this be it? Is it time to face off?

As the three dots moved closer, cameramen started wrapping their cameras in plastic. We started preparing our raincoats. Laptops were moved away from the windows, in case we would be water-cannoned out of the shoal.

VICINITY OF SABINA SHOAL

The black dots turned out to be Vietnamese fishing vessels. “False alarm,” someone yelled, and the rest laughed nervously.

So that was how it felt.

PAST SABINA SHOAL

And then they were there.

It was just a white dot on the horizon. But it glimmered under the sun. It was still too far away for any lens to capture. But it already looked different from the rest. The AM700 crew grew more serious. And the jokes from the previous days stopped for a while.

“Yung white, ina-identify natin kung China Coast Guard talaga siya. Ngayon `di pa kami sure, pero white ship siya,” said Lt. (j.g.) Sherwin Bulahan, captain of the AM700.

We were less than 10 nautical miles from Ayungin Shoal. But the white dot was closer, and fast moving in, 8.2 nautical miles away.

During the next few hours, nothing more could be heard from the bridge but the announcements about the shrinking distance between our ship and the white one.

PAST SABINA SHOAL

CREW OF THE AM700: Distance, sir, 7.8 nautical miles, sir.

4.8 NAUTICAL MILES TO AYUNGIN SHOAL

CREW OF THE AM700: Distance, sir, 7.6 nautical miles sir.

4.8 NAUTICAL MILES TO AYUNGIN SHOAL

CREW OF THE AM700: Distance, sir, 7.5 nautical miles, sir, sa puti, sir.

The white ship was not just closing in, it was steaming straight into the AM700’s course. “Papalapit po, ma’am. Salubong talaga siya, ma’am,” a crew member told me, pointing to the radar screen. “Ibig sabihin, kung hindi tayo magbabago ng course natin, magkakasalubong tayo ma’am. Papalapit po ma’am. As of now, ang distance sa atin is 6.9 nautical miles.”

By this time, the white ship was close enough for some camera lenses to capture. Marquez snapped a few shots, and zoomed it in for the sailors to see.

It was confirmed. The white ship was what the AM700 was looking at was Chinese Coast Guard vessel 1127. And it was headed our way.

At the sight of it, Gato ordered everyone to prepare. As an afterthought, he told the media to grab a bite to eat, because he knew we had a long day ahead of us.

People gathered at the forward of the ship, tense as they waited for the white dot to take the shape of a ship, and for the ship to make known its intentions. The atmosphere was an odd mixture of calm and anxiety.

Suddenly, one of the sailors yelped. And his companions broke into applause. None of it made sense in the given situation, until we noticed they were looking down in the water.

A school of dolphins had come to play with the AM700.

Everyone ran toward the dolphins, cheering them on as they raced the ship and leapt out of the water. Media and the navy clapped and whooped, temporarily forgetting the gargantuan Chinese ship making its way towards us.

“Welcome to Ayungin Shoal,” said a navy personnel out loud, as the last of the dolphins disappeared.

VICINITY OF AYUNGIN SHOAL

China Coast Guard vessel 1127 steamed so close, that its bow number and name could already be seen by the naked eye. It allowed the AM700 to pass it, and then tailed the Philippine ship from a distance. Awestruck crew members took out their cameras and snapped photos of the big Chinese ship.

I was taking videos of one such crewman, when he suddenly pointed to the right, and said “May isa pa!”

True enough, a second Chinese vessel came steaming towards us, so fast that white caps formed in its wake.

It was China Coast Guard vessel 3401. From out of nowhere, it was suddenly five nautical miles away. And it was not slowing down.

Suddenly, a crackle from the radio of the AM700.

BRIDGE, AM700

“Your action here has infringed upon marine rights and interests of the People’s Republic of China. We order you stop immediately all your illegal activities and leave this sea area. We order you stop immediately, stop all your illegal activities and leave the sea area over.”

It was vessel 3401, making a call over channel 16, and radioing us to leave what they call the sovereign territory of China.

The ship was quiet, as Lt. (s.g.) Gato picked up the radio, and spoke:

“Roger. This is Republic of the Philippines ship. We are here to reprovision our personnel aboard Republic of the Philippines ship number 57 over.”

In the silence that followed, a crew member told Gato how far the Chinese vessel was from us. “Distance, sir, 4.2 nautical miles.”

A crackle again.

“Philippine ship, your action here has infringed upon the laws of the People’s Republic of China. We order you immediately to stop all illegal activities and leave the sea area, over.”

To which Gato responded with the exact same words. “This is Republic of the Philippines ship. We are here to reprovision our personnel aboard Republic of the Philippines ship number 57, over.”

“Distance to 3401, 1.4 nautical miles, sir.”

They would speak four times, the commanding officers of China and the Philippines, each one pulling his own weight, each one not giving an inch to the other.

And then, there was radio silence. And a crewman’s last words, before everyone ran out to the bow.

“Distance to 3401, 1 nautical mile.”

BRP SIERRA MADRE WITHIN SIGHT

It was at this point when it dawned on me just how big they were, how absolutely small we were. If it took us more than 40 hours just to get here, how long would it take before any help could arrive? How far will these Chinese vessels push?

Suddenly, someone on board pointed skyward. Another aircraft was darting back and forth, but lower this time. Lenses zoomed in. It was a Philippine Navy Nomad.

“Ay, atin `yan! Yeheeeey! May kakampi tayo! PHILIPPINES!”

People on the AM700 whooped and applauded at the presence of the eyes in the sky. At least, they said, someone was watching. Should anything happen to us, people would know.

As the journalists watched, China Coast Guard vessel 3401 made a sharp 90 degree turn, and ran directly into the path of the AM700. Captain Bulahan ordered all engines off, to stop the Philippine vessel from ramming into the Chinese ship, or being sucked by the larger ship’s propellers. Once the 3401 passed, the engine was ordered back on, and Gato commanded the vessel to aim for the stern, or the back of the Chinese ship. With the 3401 unable to turn that sharply, the AM700 was able to pass from behind.

At this point, the media were already firing their satphones and satellites, with a clear realization that the Chinese had just committed an act of hostility toward the Philippine vessel. Surprised news desks in Manila started receiving phone calls from their people in the middle of the West Philippine Sea, with breaking news: the China Coast Guard has just harassed a Philippine supply ship on the West Philippine Sea.

But as everyone was making calls, 3401 suddenly made a turn so fast and so sharp that I was surprised a ship that large could be so agile. It sped up to run parallel to the AM700, and inched so close to the smaller vessel that we could see a man on board waving us away. There were at least two photographers on board their ships, too. And their deck was lined with dried fish.

From that distance, we could see the spouts of the water cannons on board as well. Filipino soldiers and even journalists flashed the peace sign toward the Chinese vessel, signifying that we were not there to pick a fight.

But from the starboard side, they crossed again, with a mere 70 yards of sea between us and their powerful engines. Seeing this, the AM700 again slowed down, waited for the 3401 to pass, then made a beeline for its rear end, making it difficult for the 3401 to turn and stop us.

We watched out for the third block, but the 3401 started moving away. It was then that the sea turned a lighter shade of blue. The AM700 had reached the shallower waters of Ayungin Shoal, making it impossible for the large China Coast Guard vessels to follow. And just like children’s book about the little engine that beat the odds and pulled the train over the mountain, the coast was finally clear for the little Philippine vessel that could.

And in the distance, there it was: the BRP Sierra Madre, old, rusty, listing to one side, and at that moment, the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.